Elizabeth Taylor

Born: July 3, 1912

Died: November 19, 1975

I was a bit unusual for a grown-up farm boy from Wisconsin. For years and years one of my foremost pleasures was reading one of the novels or collections of stories by English author Elizabeth Taylor, not the actress Elizabeth Taylor who was of little interest to me, but the fiction writer.

“I have had a rather uneventful life, thank God,” the other Elizabeth Taylor told the London Times in 1971. But, she added, “another, more eventful world intrudes from time to time in the form of fan letters to the other Elizabeth Taylor. Men write to me and ask for a picture of me in my bikini. My husband thinks I should send one and shake them up, but I have not got a bikini.”

The author Elizabeth Taylor is still known as the Other Elizabeth Taylor. But that may change.

As a writer of domestic fiction, Elizabeth Taylor was the best of her time, a latter-day Jane Austen. There have been at least a dozen “rediscoveries” of author Elizabeth Taylor in various publications, but today she still is under-recognized as an outstanding fiction writer.

What makes her writing so special?

What makes her writing so special?

Taylor’s prose is so understated and at times lightly witty yet ultimately scathing, you hardly notice that it is there. That is the definition of fine writing to me. Like Graham Greene, Elizabeth Taylor makes good writing seem effortless.

Taylor’s novel ‘Angel’ is about a really bad writer of romance novels, Angelica Deverell, who becomes famous and wealthy due to sales of her atrocious novels. A lot of authors would look upon this situation as an opportunity for very cruel comedy; however Taylor always has a deep empathy for even her most forlorn characters.

This article by Phillip Hensher is the best appreciation of the writing of the other Elizabeth Taylor that I have come across.

I wish I could write as lucidly and as straightforward as the other Elizabeth Taylor, but I do try.

Where to start with the author Elizabeth Taylor?

Where to start with the author Elizabeth Taylor?

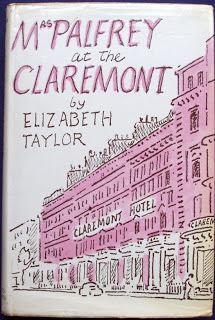

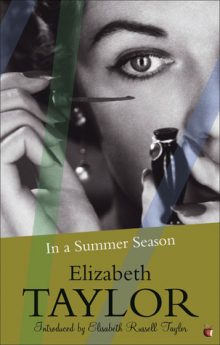

Elizabeth Taylor was consistent as well as excellent, so just about any of her books would be a good place to start. Of her novels, I can remember being particularly impressed with ‘A Game of Hide-and-Seek’, ‘Angel’, ‘In a Summer Season’, and ‘The Soul of Kindness’. Taylor was one of the very best short story writers also, so those of you who lean toward short stories might want to read ‘You’ll Enjoy It When You Get There – The Selected Stories of Elizabeth Taylor’ by NYRB.

Quotes about her

Quotes about her

Elizabeth Jane Howard once said of Elizabeth Taylor: “How deeply I envy any reader coming to her for the first time.”

“For years, the New Yorker published nearly every story she finished, 35 of them between 1948 and 1969. William Maxwell claimed that job applicants were given her stories to edit as a test, ‘and if they touched a hair of its head, by God, they were no editors’. There wasn’t much to tinker with: her style was spare, usually shorn of adverbs and adjectives, and her plots were similarly unencumbered.” – Deborah Friedell, London Review of Books

“Sophisticated, sensitive and brilliantly amusing, with a kind of stripped, piercing feminine wit.” Rosamond Lehmann

“Ruthlessness was also one of her great strengths as a writer. Far from being “charming”, her novels and stories often go straight to the rotten heart of things, fearlessly confronting betrayal, loneliness, despair and, above all, self-deception. Her prose is unshowy but wickedly subversive, quietly undermining her characters’ pretensions and wittily exposing the evasions people practise as they negotiate life.” – Peter Parker

“What did not help was that Elizabeth’s perceptions, her interests, her awareness were essentially feminine; then there is her reticence, the domestic subject matter, the lending library aura that surrounds her work, the Thames Valley settings, the being married to a sweet manufacturer….the assumption that her work is predictable…one could go on. And as for her style, too many reviewers found it too feminine, missed the humour, missed the bleakness, could only see the subject material was domestic and then condemned the entire oeuvre as minor, certainly incapable of greatness.” – Nicola Beauman

Quotes from Elizabeth Taylor herself

Quotes from Elizabeth Taylor herself

“I’ve no imagination and can only write of what I know.”

“I never wanted to be a Madame Bovary. That way for ever—literature teaches us as much, if life doesn’t—lies disillusion and destruction. I would rather be a good mother, a fairly good wife, and at peace.” – Elizabeth Taylor, A Game of Hide-and-Seek

“The secret of your power over people is that you communicate with yourself, not your readers.” – Elizabeth Taylor, Angel

“The whole point is that writing has a pattern and life hasn’t. Life is so untidy. Art is so short and life so long. It is not possible to have perfection in life but it is possible to have perfection in a novel.”

Recent Comments